Most tech companies make this fundamental messaging error—does yours?

By talking about things other than tech, you’ll earn yourself far more opportunities to talk about your technology, but at the right time and with the right people.

I’m gonna start this post with a provocative statement: almost 60% of ‘tech companies’ in the Waterloo Region don’t understand what market they’re really in.

And that’s a problem.

In fact, it might be the most fundamental problem facing the region’s tech companies, because how we think about ourself has an enormous influence on how we present ourself to the outside world—in this case, potential customers.

In this post, I’ll:

- Explain what I mean

- Present data to back up my seemingly outlandish claim

- Explore the sneaky and terrible impact of this widespread problem

- Suggest a plausible reason why this problem is so prevalent

- Propose an easy approach to fixing it

But first, let’s begin with a quick discussion that sets the stage for the subject.

What is ‘Tech’, Anyway?

“We’re really mostly a content company powered by tech” —Reed Hastings

We’ll start with a high-profile example: in a recent interview with Recode, Netflix CEO Reed Hastings said that, “we’re really mostly a content company powered by tech.”

But isn’t Netflix a tech company? After all, they often get lumped into the same conversations as Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, et al.

They’ve definitely built some neat technology, but the numbers don’t lie: Netflix spends $1.2 billion a year on technology and around $10 billion on video programming (content production, licensing, etc.). So they’re a content company, in the entertainment market.

OK, now let’s look a little closer to home. When I was researching and number-crunching for The Waterloo Region Technology Marketing Spotlight, I had to make some subjective judgements. Quoting from the study’s explanation of methodology:

One key subjective consideration is: where do we draw the line between a technology company and a company that simply uses technology? We tried our best to apply a consistent ‘test’ that assessed whether technology was an output or major defining characteristic of a company, or merely a tool. This distinction meant that companies like Sun Life and Manulife are omitted.

By employee count, Sun Life and Manulife probably employ more tech workers than any of the region’s ‘tech’ companies, with the likely (but not assured) exceptions of BlackBerry and OpenText—but I haven’t heard anyone try to make a serious argument that they’re tech companies. And, for the record, I worked at Sun Life back in the day as a Java Developer.

Personally, I think we’re all too quick to assign (whether to our own company or to others) the ‘tech’ label: I think there are tech companies, but that the vast majority of companies labeled as ‘tech’ companies are something else.

After publishing my study, I had a conversation with Eamon O’Flynn of the Waterloo EDC (which led to this article) in which he inquired along the same lines:

Eamon: How did you ensure a company was a “tech company” and does that mean non-tech companies that are in Waterloo to do tech-specific work aren’t included in the numbers?

Me: Yeah, it’s a real challenge and subjective decision. Folks who primarily do a big thing, and dabble in tech as part of R&D weren’t included. And, unfortunately, there’s a huge and varied spectrum from “OK, definitely tech” to “Giant corporation that obviously uses tech, but it’s more an enabler than a focus.”

It’s clear I’m definitely not the only person who’s grappled with the issue.

So, why did I just spend a couple of hundred words on this topic?

This pervasive idea that everything is tech distorts our thinking and exerts enormous influence on how we see the world, how we see ourselves, and—crucially—how we attempt to reach our target markets.

Because this pervasive idea that everything is tech distorts our thinking and exerts enormous influence on how we see the world, how we see ourselves, and—crucially—how we attempt to reach our target markets.

It is a major cause of the problem I’m hoping to solve (or at least to which I’m trying to call attention) in this post.

Markets—Who You Serve vs. What You Serve vs. How You Serve

Let’s quickly look at a few important and distinct characteristics of your company:

- For whom you do things: the types of customers you serve

- What you do: the solutions you provide, in terms a layperson would understand

- How you do it: the specifics and implementation details of your approach to providing solutions

Your messaging should be very much about the first two, and very little about the third. Oh, and I’m not gonna get into that Simon Sinek why soundbite BS…most customers care much more about what you can do for them than why you do it…truth-bomb!

How you do something is where you talk about technology, and it’s much, much less important than what you do and for whom. That collection of ‘whoms‘ is your target market (or maybe you can break the whoms into groupings based upon common characteristics, so then you’d have multiple markets).

Getting in front of your whoms and telling them what you can do for them is a proven way to build your business; blathering on about how you do stuff is a great way to feel busy and achieve very little.

Getting in front of your whoms and telling them what you can do for them is a proven way to build your business; blathering on about how you do stuff is a great way to feel busy and achieve very little.

My observation is that most—not just some—of Waterloo Region’s tech companies focus on talking about how they do stuff rather than what they do.

Sobering Statistics

The fact of the matter is that an enormous number of companies have picked the wrong industry, and the sooner we recognize and correct that, the better.

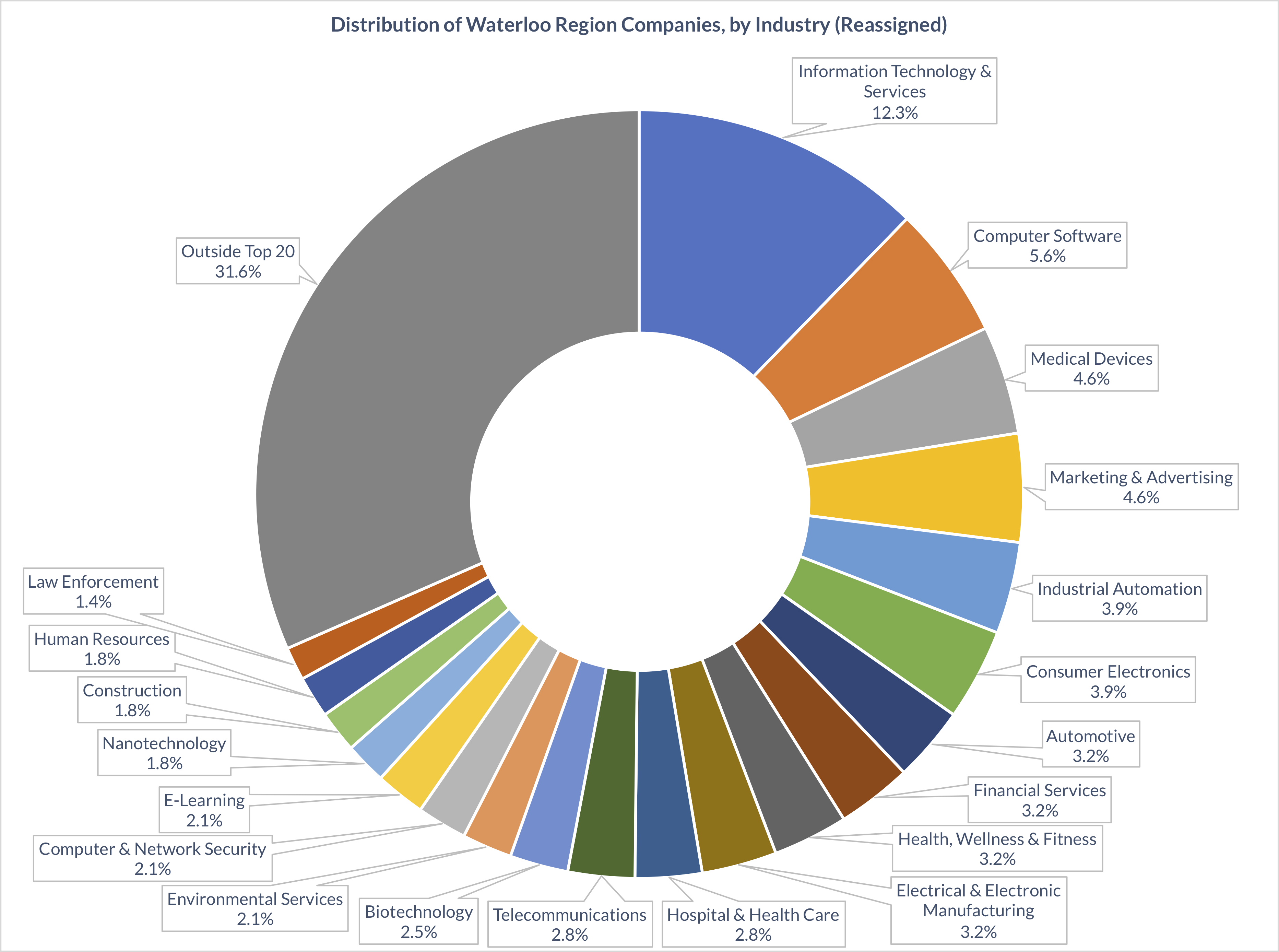

While researching for my spotlight study, I exhaustively catalogued every tech company in the region according to LinkedIn’s “Industry” designation: notably, in addition to recording the self-identified industry for each company, I also investigated the company more deeply and—where applicable—assigned a more appropriate industry from the LinkedIn list.

Does that sound arrogant, that I would wade in and assign an industry? Well, so be it. The fact of the matter is that an enormous number of companies have picked the wrong industry, and the sooner we recognize and correct that, the better.

Now, a minor caveat: unfortunately, LinkedIn is pretty lousy when it comes to how they handle industry designations. First, the industry list is terribly limited (and sometimes downright bizarre, if you really look into what’s there and what isn’t). Second, each company can only choose one industry.

Sadly, these limitations force a large number of companies to ‘legitimately’ pick one of the generic tech-related industries as the least worst option.

For instance, companies who serve very particular markets are at the mercy of the list—if your market’s not there, then some generic crap might be the best you can do.

Companies who serve more than one market have a different bind: do you pick one market above all others, or go generic? (for whatever it’s worth, Waterloo Region’s companies took each approach with about equal frequency)

Maybe take two moments right now, and:

- In the first, think about your company, and specifically think about the markets you serve: who are your customers? what market would they choose to describe themselves?

- In the second, go to your company’s LinkedIn profile and see what Industry you’re telling the world you’re in

If your industry matches your customers’, then you’re in the minority: ultimately, my (admittedly subjective, but shaped by some pretty solid tech marketing experience) conclusion is that 57.8% of Waterloo Region’s tech companies chose their industry designation based upon their underlying technology rather than by the market that they actually serve. That is, only 42.2% are market-oriented.

Yikes.

Here’s how the self-reported industry breakdown looks:

And here’s how my ‘reassigned’ version looks:

Let’s examine some of the obvious differences:

- The reassigned version shows a much richer list: the top 20 industries only account for fewer than 70% of companies, versus more than 80% in the self-reported version

- While 17.9% of companies still fall into the generic Information Technology and Services or Computer Software, or Internet in the reassigned version, that’s a far cry from more than 40% in the self-reported version

These first two results suggest that more of the region’s companies participate in more markets than we’d know if we just went on the self-reported industry designation on LinkedIn.

When we choose our industry based upon our how, rather than our for whom or our what, we tell a much more boring story about our companies individually, and about the region as a whole.

What else can we see, if we look more closely? Mainly, many industries have more local companies than we might realize—look at the industries that got significant bumps: Industrial Automation; Consumer Electronics; Automotive; Financial Services; Health, Wellness & Fitness; Hospital & Health Care; Telecommunications; Environmental Services…and more!

When we choose our industry based upon our how, rather than our for whom or our what, we tell a much more boring story about our companies individually, and about the region as a whole.

Also, it’s generally better to go with the for whom than the what. In a few of the reassignments, companies had picked a what (say, Medical Devices) rather than an arguably more appropriate whom (say, Hospital and Health Care).

Is my classification perfect? No. But I’m definitely not sufficiently wrong as to undermine my broader point that too many companies take a technology-oriented view of themselves, versus a market- or industry-oriented view.

So What—Does it Even Matter?

Yes!

Misidentifying one’s own industry or market is both a cause and an effect:

- It’s an effect (or symptom) of our love of all things tech, and our natural inclination to align ourselves with tech because it’s cool, innovative, and at the core of our solutions

- It’s a cause of enormous messaging problems that have an outsized influence on how we communicate with our market, and it might well be the major reason why so many ‘tech’ companies struggle to reach their potential customers

When we self-identify as ‘tech’, it shapes everything we do—we’re far more likely to see everything through the tech lens.

Here’s an example of the type of influence this outlook can have.

A few weeks ago I was at the ProductTank Waterloo session to hear April Dunford speak about positioning (a great session, by the way). She shared an example that illustrates a problem she regularly encounters working with tech companies: as part of the positioning process, she’ll ask a company what alternatives are available to prospects other than choosing the company’s solution; most of the tech companies go on to list other, similar tech companies as the prospect’s alternative.

Most tech companies list other, similar tech companies as the prospect’s alternative. What’s wrong with that? Well, it’s only partially correct and almost certainly largely wrong.

What’s wrong with that? Well, it’s only partially correct and almost certainly largely wrong. No matter who you are as a tech company, here’s a much more accurate list of your prospect’s real alternatives:

- Do nothing—the prospect just keeps living with the pain

- Solve it internally—the prospect initiates some sort of project, or hires some people, to address the problem

- Buy from a behemoth: Oracle, Microsoft, SAP, Huawei, Cisco…some giant will already do what you do (or will offer to build it)

- Find a solution from a company like you (but your prospect probably hasn’t heard of them)—and it’s entirely likely that this alternative represents a very small minority of outcomes

See what happens when we over-focus on tech? We miss the bigger picture, and we unknowingly and artificially limit our thinking.

When we over-focus on, we miss the bigger picture, and we unknowingly and artificially limit our thinking.

So when we think of ourselves as tech companies, it causes us to focus on our technology (our how), which leads us to lead with our technology in all our marketing messages and communications. What this means, in reality, is that we’re basing our entire future on this erroneous, implicit assumption that our prospects already have such a good understanding of their problems that they’ve identified the technological characteristics of the ideal solution, and they’re looking for that.

When you talk exclusively about your technology, you’re talking almost exclusively to Early Adopters. They’re hip, they’re with it, and they represent a small fraction of the market.

Yes, there are prospects like that—they’re called Early Adopters. They’re hip, they’re with it, and they represent a small fraction of the market. When you talk exclusively about your technology, you’re talking almost exclusively to Early Adopters.

As I said earlier, as part of my study I exhaustively researched hundreds of tech companies in the Waterloo Region. That involved going to every single company’s website and learning about what they do, how they do it, and for whom they’re doing it. The unfortunate reality is that far too many of the region’s companies orient their entire message around how they do, rather than for whom and what.

The unfortunate reality is that far too many of the region’s companies orient their entire message around how they do, rather than for whom and what.

I hummed and hawed over whether or not to include real-world examples, but ultimately decided against doing so—I didn’t want it to look like I’m picking on anyone in particular, when the problem is enormously pervasive. Instead, I’ll close off this section with some pithy suggestions.

You’re not a Computer Software company, you’re an Automotive company.

You’re not an Internet company, you’re an Education Management company.

You’re not an Information Services company, you’re a Leisure and Travel company.

You’re not a Computer Hardware manufacturer, you’re a Telecommunications company.

You’re not an Information Technology and Services firm, you’re a Health, Wellness and Fitness company.

And so on. See the difference in meaning?

Potential Origins

I’m gonna speculate here that the origin story of most tech companies goes like this: cool piece of tech → turn it into a product → wrap a company around it to build, sell, support (and so on) the product.

Additionally, an enormous proportion of tech companies are founded by engineers.

So it’s not surprising that we identify with tech, if it’s literally the origin of the company. It’s only natural that the tech itself dominates our stories and shapes our perspective, how we see ourselves, and the messages we send.

But natural and right aren’t the same thing in this case, and leading with tech is a mistake.

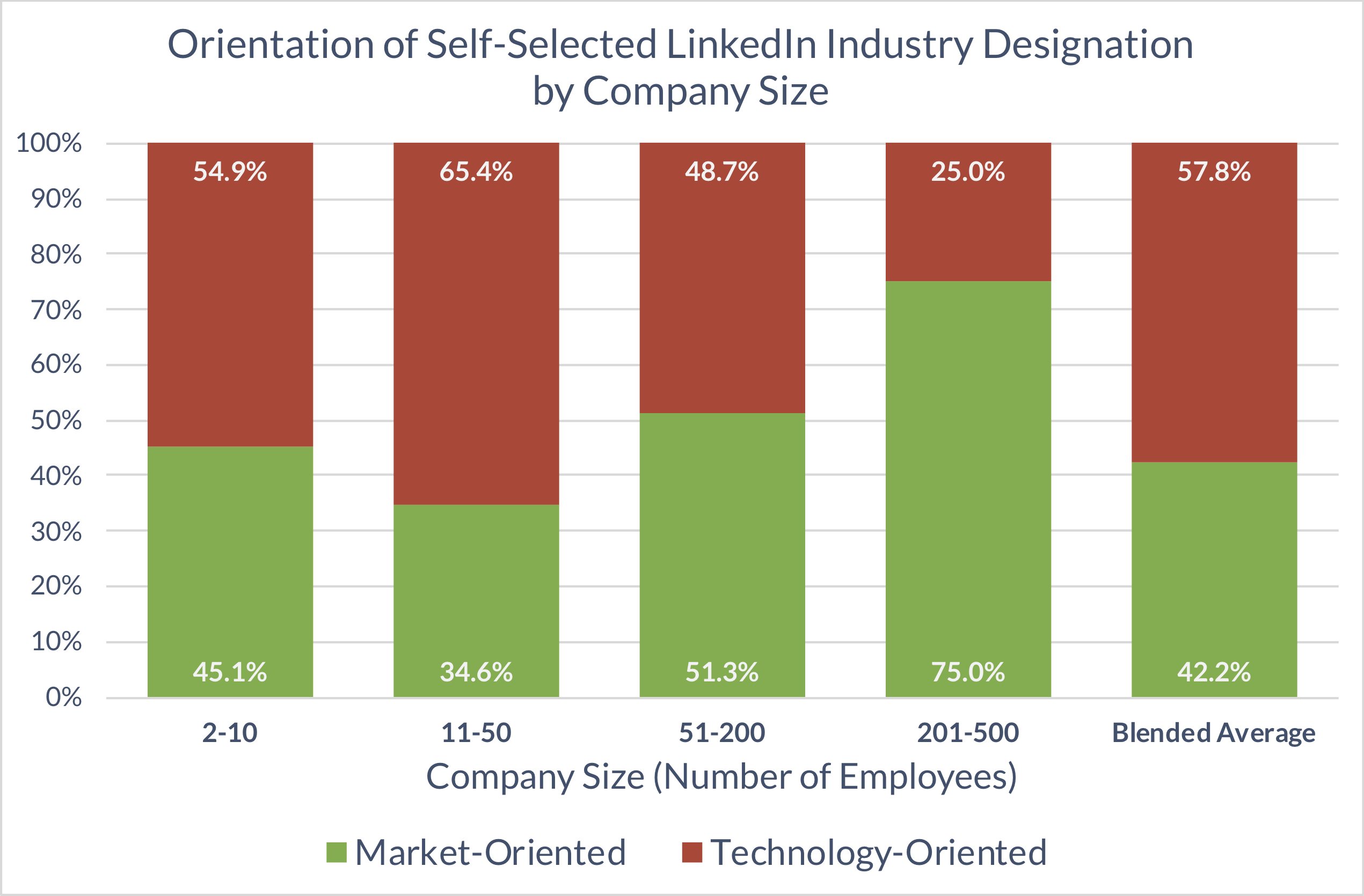

Here’s another fun chart:

OK, broadly (although a bit weakly), it looks like the bigger a company is, the more likely it is that its industry designation on LinkedIn is market-oriented rather than technology-oriented.

The bigger a company is, the more likely it is that its industry designation on LinkedIn is market-oriented rather than technology-oriented.

Here are two potential explanations:

- Companies with market-oriented industry designations on LinkedIn are more successful (i.e., using the proxy of employee count)—maybe this designation represents their thinking, in general?

- As companies grow and mature, they come to better understand what market they’re really in, and update their LinkedIn industry designation accordingly

For what it’s worth, I also examined the results by company age, and found much weaker correlation…so the “older companies are wiser, and are likely to be bigger” explanation doesn’t work.

The Fix

Some folks probably don’t think there’s a problem here—I honestly don’t understand how anyone could think that, unless they’re utterly underestimating the importance of marketing in general, and messaging in particular. “Oh, what’s the big deal?” The big deal is that not correctly recognizing your own market is a pretty enormous and fundamental mistake, and it’ll exert enormous influence on all aspects of your marketing and communications.

The big deal is that not correctly recognizing your own market is a pretty enormous and fundamental mistake, and it’ll exert enormous influence on all aspects of your marketing and communications. If we can’t get something as simple as identifying our market or industry correct, then what hope do we have of tackling legitimately complex marketing problems?

Others might agree that there really is a problem, but see it as fairly innocuous. Sure, I can get that…we can have different opinions as to the severity of the issue. But let me just say that if we can’t get something as simple as identifying our market or industry correct, then what hope do we have of tackling legitimately complex marketing problems?

Here’s my fear: that this whole thing—both the statistical LinkedIn stuff and the far-more-serious-but-harder-to-quantify issue of the lousy messaging I saw on hundreds of websites—is just a symptom that we don’t take marketing seriously.

If you ever want to cross that chasm, then you’d better start talking about market problems, rather than technology.

And if that’s the case, then bummer, because if you ever want to cross that chasm, then you’d better start talking about market problems, rather than technology.

But the good news is that this problem is actually really easy to fix: as with many things marketing, you just need to take an outside-in approach.

As in the two-moment exercise above, think of your customers. Who are they? How do they describe themselves? How do others describe them?

Now, look at yourself as a member of that group, of that market, of that industry, rather than some ‘tech’ company that just sells some ones and zeros from afar. And I mean really put it on. Get into it. Tap into that grade 9 drama experience and really, truly get into character. Feel—nay, experience!—the industry’s pain.

Let this new perspective shape your messaging and your communications: talk about the market, talk in terms that show you’re a part of that market, talk about market problems, talk about what solutions you provide.

And don’t worry, you’ll still get your chance to talk about tech—and that’s maybe the central irony here: by talking about things other than tech, you’ll earn yourself far more opportunities to talk about your technology, but at the right time and with the right people.

Think of your customers. Who are they? How do they describe themselves? How do others describe them? Now, look at yourself as a member of that group, of that market, of that industry, rather than some ‘tech’ company that just sells some ones and zeros from afar. Tap into that grade 9 drama experience and really, truly get into character.

—

Header/Featured image credit: Photo by NeONBRAND on Unsplash